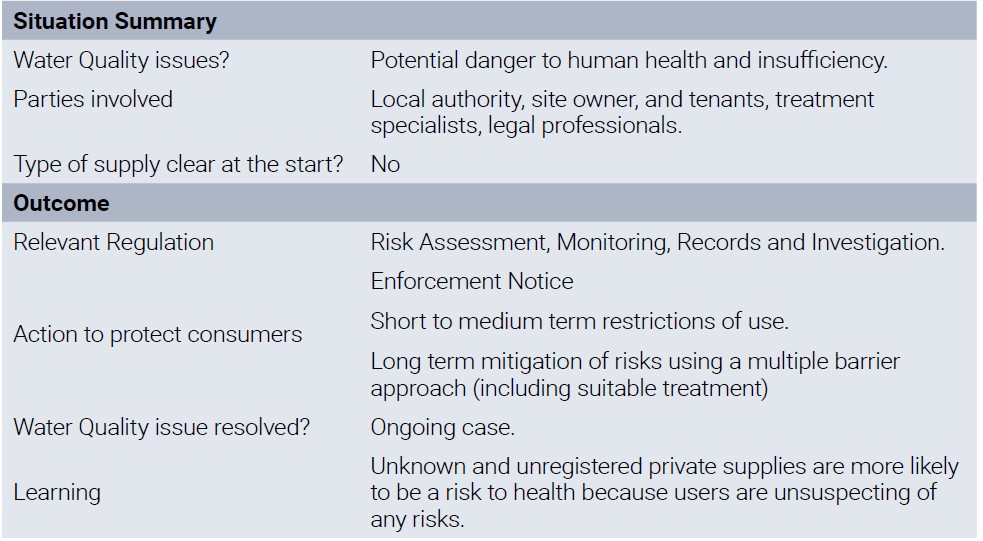

An established private water supply discovered during CoViD-19 pandemic “Lockdown” restrictions

Introduction

This case study concerns a large, commercial and public use supply in the north of England, which until April of 2020, was not known to the local authority. The supply is a spring source which feeds several properties one of which belongs to the owner and at least one which is rented together with a fishing lodge and toilet block. By definition this is a supply is provided as part of a commercial activity. Officers were first alerted when they received a report of water insufficiency from a tenant occupying one of the buildings. The local authority did not initially attend site to investigate, observing the Government’s advice to stay at home at the start of the pandemic. However, a risk assessment was undertaken through a desk top study to identify any potential hazards.

Local Authority action

In June 2020, the local authority attended the site and conducted a survey to complete the risk assessment. During this visit the source was found to be located within dense woodland, (See Figure 1), with no source protection in place and no spring collection chamber. Surface water was noticeably ponding above the spring creating an immediate and uncontrolled hazard. As part of the normal operation, water is pumped up the hill solely using power generated by a wind turbine (See Figure 2) which is likely to be inconsistent due to the inherent dependency for wind. Once up the hill, water is distributed to several tanks (See Figures 3 and 4) in different locations, all without secure covers and some which were located on the bank of a landfill site. There was no evidence that the tanks had ever been cleaned and there was no treatment of any kind.

Samples were taken for a range of chemical and microbiological parameters from a representative point at one of the properties which found: coliforms, (42 /100ml) including E. coli, (17/100ml) and enterococci (9 /100ml). E. coli and enterococci are indicative of faecal contamination and represent a potential danger to human health. As an immediate mitigation the local authority delivered written advice to all consumers to boil the water before consumption. The findings by the local authority were serious and required a longer-term plan to protect the consumers. This included the consideration of what measures were necessary, who constitutes the responsible person, how these measures could be facilitated and how these should be written into a formal notice to secure public health.

The overriding objective in such a complex and unmitigated situation is to specify the outcome and the steps to secure the supply in order to protect public health in a Notice, and then serve the notice which the local authority proceeded to do. In this the Inspectorate were able to offer advice, working together with the local authority on the necessary remedial measures to ensure a multiple barrier approach was applied, including the installation of suitable treatment to meet the raw water challenges identified by the risk assessment. Supplemental to this included the need for the owner, who is the responsible person, to implement contingency arrangements for insufficiency, along with suitable management and maintenance procedures once a system of treatment was put in place.

Even though a notice is served, solving such a difficult situation with a private water supply is rarely easy for several reasons, and this example is no different. The core difficulty is most often the cost; then lack of cooperation by the relevant person which is often linked to cost; knowledge of water treatment and what to do to secure a safe supply; assured contractors to carry out any work and finally ongoing maintenance which require itself suitable and competent contractors.

Dealing with this specific example: The most sensible solution for a supply which presents such a serious risk to health is to consider putting the supply onto the public mains. This can be difficult most often due to the remote locations of some supplies but should always be considered. In this case the cost as estimated after enquiries by the local authority, was found to be £500,000 and so this option was not feasible for the local authority nor the responsible person.

Consequently, a notice to improve the supply was the only pathway. The expectation after serving a notice is for the responsible person to act within the specified timescale. By September 2020 the deadline for the owner to complete the remedial works had passed. The local authority returned to site only to find that the owner had not completed any work. By this time, relations between the tenant and the supply owner (his landlord) had also deteriorated significantly, with the tenant claiming that the owner had cut off his supply on seven occasions. The tenant was in fact due to be evicted in early November but due to the pandemic, the court case couldn’t be heard.

Although the supply was a potential danger to human health, as so often is the case, the owner was unwilling to carry out any remedial work to address these risks. There are two options open to the local authority: One is to take court action on the failure to comply with a notice; the second is to complete the work at the expense of the local authority and subsequently to recover the costs (known as works in default) at some point in the future. Neither are ideal solutions, can be protracted, and are uncertain particularly in recovering costs, during which there is a continuing risk to public health.

In this case, the local authority invested a significant amount of time in investigating a suitable contractor to advise and estimate the necessary work. This is because the responsible person following the return visit did begin some remedial work on the supply himself in the face of being prosecuted, but the local authority had no confidence in the owner’s intensions or his approach to remediating the deficiencies.

There is no national body for water treatment engineers, like the “Water Safe” scheme for plumbers, that either a local authority or supply owner can be directed to. This is not unusual and is the same for a public water supplier when sourcing contractors. A public supplier under the Water Industry Act 1991 remains directly responsible for supplying wholesome water which if unfit, is a non-delegable offence, even if a contractor is used to carry out work on their behalf. Nevertheless, a public supplier has the knowledge and resource to employ and supervise contractors to the expected standard. A private supplier is required to complete the requirements of a notice set by the local authority upon which, not to do so is an offence. Beyond that, the responsibility is a matter of a responsible person’s duty of care and as a small concern, they may not necessarily have the skill, knowledge, resource or ability to contract and assess the work.

The local authority’s investigations in considering carrying out the works in default was estimated to be in excess of £30,000, an amount that the local authority was understandably not prepared to spend. However, in December 2020 the local authority met with a water treatment engineer on site to discuss possible source protection measures and treatment options with the responsible person and was met with an extremely aggressive and confrontational owner. He would not agree to the possible solutions put to him by the local authority and treatment engineer.

The water treatment engineer recommended that rather than building an extensive treatment plant room to serve the entire site, pre filters and UV units could be installed in each domestic property. This work was carried out by February 2021, by which time a new family of four had moved in. The owner of the site confirmed on numerous occasions that he did not want any treatment at his own property.

Throughout the duration of their investigations the local authority had on several occasions to provide bottled water to the tenants when the owner apparently severed the supply to users. This incurred a considerable amount of time engaging with Public Health professionals, Community Teams and Social Services as there were children involved. In addition to this, quotations for bottled water from external suppliers had to be sought through collaboration with the local water company.

Registration of private water supplies

The existence of supplies unknown to local authorities is a clear gap in regulating and remediating supplies which may be a harm to health as this case study demonstrates. Regulations require local authorities to keep a record of every private water supply in its area, however, it is not a regulatory requirement for owners to register them. Furthermore, local authorities are not required to seek out supplies or to use their enforcement powers to compel registration of any new or existing supplies that they become aware of in their areas. As such, the extent of supplies that are not registered with local authorities is unknown.

Information on private supplies is largely sourced from historical records and local knowledge, or through other regulatory visits such as food inspections, or as this case shows, in response to complaints or concerns about quality or insufficiency by users. This is because owners and users do not always make local authorities aware of them particularly if the supplies are in remote rural locations. This is either because the owners are unaware that they must do so, or they consider that any notification to the local authority may result in additional unplanned costs with the imposition of requirements.

This gap was partially closed in 2016 in England and 2017 in Wales when revised regulations introduced a requirement for local authorities to apply their regulatory obligations to all newly installed supplies, and those that had been out of use for 12 months or more. Nevertheless, this regulation (Regulation 13) only becomes applicable once the local authority has become aware of the new supply. If, however a local authority at any time does become aware of a previously unknown supply it can, if necessary, use powers of entry and to gain information under sections 84 and 85 of The Water Industry Act 1991 respectively to carry out their regulatory obligations.

Learning

This case study illustrates an example of a previously unknown private supply which constituted a serious risk to public health which came to light through a complaint to the local authority. This was complicated by CoVid-19 pandemic restrictions and exacerbated by the owner’s aversity to engage, further compounded by civil disputes between the supply owner and users. Unknown and unregistered private supplies are more likely to be a risk to health because risks are not identified by competent assessors and there are no controls in place to mitigate any risks. The Inspectorate has previously sought to facilitate a means of ensuring that new borehole/private supplies were registered in some way through liaison with The British Geological Society, Environment Agency and The Well Drillers Association to determine whether this deficiency could be rectified or not. Unfortunately, it found that none of the organisations represented were able to commit to a way forward, as they did not have adequate resource to follow up owners of boreholes who failed to notify newly installed boreholes or supplies. Until there is a clear mechanism requiring any private supply to be registered with the local authority, the situation of high-risk supplies which are a potential risk to health will remain.