Case studies: a private supply used as part of a public activity

Water Quality Issues | Supplies that constitute a potential danger to human health. |

|---|---|

Parties involved | Local authority, the Inspectorate, supply consumers, a supply managing agent, landowners, the local authority Ombudsman. |

Supply type | Regulation 9 (due to public use). |

Relevant Regulations | Regulations (England) 2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 12, 13, 14, 16 and 18. |

Action to protect consumers | Restriction of use, remedial work on the supply assets, the need for management and maintenance of supply, and associated record keeping. |

Water Quality issue resolved? | Ongoing |

Learning | The diverse nature of private water supplies where they are provided to the public for domestic use, the range of stakeholders and complexities around ownership and where or if the regulations apply. |

Introduction

Specific and often unique circumstances can sometimes make it difficult to determine whether a supply of water, other than a public supply, falls within scope of the Private Water Supplies (England) Regulations 2016 (as amended) and The Private Water Supplies (Wales) Regulations 2017 (the Regulations) or not. This situation often arises where supply arrangements or the reason for the water’s provision is uncertain or it has changed or is disputed, or where no apparent supply owner exists. Similarly, where new and or temporary supplies are intended for specific sanitary purposes, it is not always clear to local authorities whether sampling and risk assessments are required or not. In 2021 the Inspectorate was sighted to several such examples, each raised as an enquiry by local authorities seeking clarity in how the regulations were applicable, if indeed they were at all. The following three cases studies share this theme, each different in nature, but all concerning use of the water by the public.

Case study 1: a supply with an unknown source

The first of these case studies concerned a flow of water emanating from a pipe on a canal bank in southwest England (Figure 1). This was located on Canal Trust land and believed, but not verified at the time of the enquiry, to be a water company asset. Although this did not appear to be a designated public amenity, it had nevertheless long become common practice by canal users to collect water in containers for domestic purposes from this point. The local authority was informed by the Canal Trust that they had erected signage stating that “the water was not safe for drinking purposes”, but because they had put the local authority phone number on the sign, users were contacting them to say that they had been drinking it for years and would continue to do so. The Inspectorate was asked if the signage was sufficient to mitigate the Canal Trust liability and whether the private water supplies regulations should be enforced as for a drinking fountain.

The Inspectorate advised that the wording of regulation 3 (Scope) was key in this instance, as it describes that a supply is only within scope of the regulations where the water is intended for human consumption.

The sign that had been erected by The Canal Trust implied the water was not for human consumption. The Inspectorate advised that that the Trust should clarify the origin of the water, identify the owner of the pipe and establish whether any provision had at any time been made for the water to be used as for public use.

The Inspectorate also advised that the local authority investigate the supply arrangement upstream and establish if it was a private water supply (as detailed in regulation 2). Sampling was recommended to confirm if the water met the regulatory standards and presented a potential danger to human health as the signage installed by the Canal Trust implied. If this was the case, the local authority should, in its Environmental Health capacity, place a more permanent sign beside the pipe to deter canal users collecting water from it, or alternatively arrange for the water to be diverted elsewhere, if feasible. Although it seemed unlikely that this water was within scope of the private water supplies regulations, should this not be the case, it was essential that the regulatory requirements of new supplies (regulation 13, or 15 in Wales) were initiated, and the responsibilities of all relevant persons agreed to protect public health by taking actions necessary to safeguard the quality of the supply.

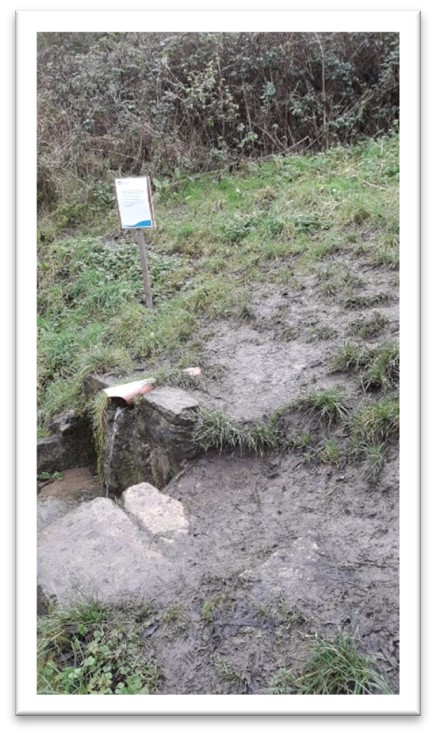

Case study 2: a supply provided at a public waterspout

This second case concerns a waterspout located a roadside in central England (Figure 2). This historical feature was created by a Nineteenth Century Act of Parliament to provide a public supply of drinking water prior to the construction of modern licensed public supplies. Untreated water still emanates from the spout, which creates a historical local feature and is much used by the public to collect water. This attracts visitors to the area, including coach parties, which stop off at the spout to view and “experience the waters.” This in turn brings tourist revenue to the local town. Local historical groups promote the spout and seek to preserve historical beliefs associated with the nature of the water. Although the spout is located on land owned by a conservation trust, the ownership and responsibility for the upkeep of the supply itself is, however, a matter of conjecture in the apparent absence of any records. To further complicate matters, although the actual source of the supply is thought to be from one or more local springs, their locations are not known.

The local authority initially believed that the supply probably did constitute a private water supply based on guidance provided on the Inspectorate’s website. They had served a regulation 18 notice on the “relevant person” as sample results suggested that the supply was a potential danger to human health. This “relevant person” however claimed not to have any responsibility to mitigate the risk on the grounds that the supply was fed from an underground reservoir owned by a water company. This asset they believed had been transferred from local authority ownership to the predecessors of the water company in 1974. By this reasoning they asserted that any notice served by virtue of the private water supply regulations was invalid.

Unfortunately, the local authority was unable to find any records to authenticate this alleged asset transfer, and the water company considered it unlikely that they would have assumed responsibility for an obsolete supply of water at the time of the alleged transfer, although they too had no records to substantiate the claim either way. It was concluded by the local authority that all parties were assuming that responsibility for the supply lay with others not them, and that this had probably been the situation for decades until the post 1991 private water supply regulations had brought the issue to the fore.

Whilst investigations into asset ownership were ongoing and until a longer-term solution could be established, the local authority affixed a temporary sign next to the spout deterring any consumption of the water by the public. On the advice of their legal team the local authority at this stage, proposed that they serve a regulation 18 notice on the water company as the landowners. It was later decided not to pursue this whilst discussions to clarify the supply arrangements and asset ownership were ongoing. As part of the ongoing investigations, the local authority contacted the Inspectorate in November 2021 to confirm whether the waterspout constituted a private water supply or not, as they had previously interpreted. However, in the absence of a substantiated supply schematic and any written agreements regarding ownership and supply management, the Inspectorate was unable to provide further clarity.

The inspectorate suggested that the local authority sought a clearer understanding from all parties concerned as to what they considered the current purpose of the waterspout to be. For example, was this a provision of a supply of water for human consumption, or was it simply a visual reference to an early water supply, no longer considered suitable for those purposes?

The Inspectorate acknowledged that in general terms a water fountain not fed by a public supply was, in most circumstances, a private water supply, but advised that this is only applicable where the water is intended for human consumption, as defined in regulation 3 of the Regulations. Should the relevant parties agree that this was no longer provided for these purposes, then any visitor to the attraction should be deterred from using it as such by way of suitable permanent signage, or by its disconnection. Should this not be agreed, or permitted however, then it must be regulated by the relevant regulations – either for private or public supplies, for as long as the water is intended for those purposes. By January 2022 asset ownership of this supply was still uncertain and clarity was being sought through legal professionals acting for the parties concerned.

Case study 3: rainwater harvesting for partial domestic use

This case study also concerns a private water supply that forms part of a public activity. It relates to another enquiry received by the Inspectorate in 2021 and concerns a temporary event in London.

During 2021 a London Borough local authority contacted the Inspectorate regarding its intention to hold an outside public event for a limited duration. The authority intended to use this water as part of a public amenity for handwashing toilet flushing purposes, but not other domestic purposes, and asked whether this would require the supply to be risk assessed and monitored. By so doing this would (a) be taking a sustainable approach to water use at the event (b) save considerable costs.

The Inspectorate confirmed that the proposed arrangement did constitute a private water supply and so was therefore subject to the requirements of the private water supplies regulations. Whilst the Inspectorate agreed that the authority’s intensions to use water in a sustainable manner, it was nevertheless necessary to maintain public health standards in line with primary legislation and regulatory requirements.

The Inspectorate regularly receives enquiries from local authorities asking if it is permissible for the Regulations to be relaxed where a private water supply is intended only for sanitary purposes. Any interpretation of the regulations and how they are applied is at their discretion as regulators, but they are advised to use the Inspectorate’s guidance to assist with any decisions in this respect. It is the Inspectorate’s view that water intended for any domestic purpose, be it sanitary purposes in isolation or not, should meet the requirements of the regulations.

In this instance it was advised that a risk assessment for the supply must be carried out, and that any monitoring arrangements be established in accordance with the regulatory requirements of the supply type, and on a risk a basis.

Learning and summary points

These case studies illustrate the diverse nature of private water supplies where they are provided to the public for domestic use. Every case presents its own unique set of issues that must be assessed to determine where, or how, the regulations apply if at all. Any lack of clarity over supply ownership, current asset arrangements and the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders can complicate the application of the Regulations.

Case study 1 concerned a situation where water of an unknown source was being used for human consumption by the public. Its use in this way appears to have developed over time, perhaps due to its convenient location. Here the local authority acted appropriately in the first instance by restricting its use. It then approached the Inspectorate for guidance on how or if the regulations were applicable. The local authority was advised that the criteria specified in regulations 2 and 3 of the regulations were key to this decision-making process. In this example, it was necessary for the local authority to collaborate with other stakeholders including The Canal Trust and the local water company to identify the source of the water, and whether it had any purpose in the context of a public activity at all. This case study has shown that a local authority may sometimes need to consult several parties and invest further time in its investigations before any decision regarding the application of the regulations can be reached. Agreements for the future use of supplies of this nature will then need to be agreed by all relevant parties.

The second case study concerned a public waterspout, which forms a local heritage attraction, the responsibility for which was not clear. This is not uncommon on small-shared supplies to dwellings, but here, by contrast, is an example of a regulation 9 supply where users constituted a transient population. This means that they are comparatively less likely to be immune to any pathogens that may be present in the supply and are therefore at greater risk.

This case study exemplifies an historically significant supply being used for public consumption where it’s domestic use in this way is no longer essential. Furthermore, in this example the supply was unsafe to be used for human consumption without suitable treatment. Although the feature itself remains important for the purposes of local tourism, ownership for the management of the water was shown to be lacking. This, over decades led to the deterioration of its quality, giving rise to it being a potential danger to human health. This has led to difficulties in establishing who is responsible for improvements to mitigate these risks under current legislation. Here, the provision of a municipal mains supply to the area has long since negated the need for a common community water point, as it was originally intended. However, tourists regularly stop by at the spout to collect water in containers for later use. Therefore, if it is agreed by all stakeholders concerned that the water is to remain available for public consumption for these and other traditional reasons, then these issues must be overcome.

The third example in this group of case studies highlights that private water supplies legislation does not always align with current aspirations to use water in a sustainable way. Similarly, it appears not to promote sustainable or cost-effective remediation to achieve reliable wholesome private water supplies. The primary legislation (The Water Industry Act 1991) is now 30 years old, and the post 1991 regulations have been in place for 10 years. In 2022 the Inspectorate intends to commission a project which will undertake a review of the private water supplies legislation and its effectiveness in maintaining safe, wholesome, and sufficient supplies.