Case study 8 – Risks associated with change of use from a supply for non-domestic purposes to domestic purposes

This case study illustrates some examples of the legacy of historical deficiencies of the private water supplies legislation prior to the current legislation. This is illustrated in relation to a regional industrial group of Regulation 9 supplies located in south-east England. These supplies serve an area of salad growing nurseries, which supply produce to some of the large supermarket retail outlets. The supplies are fed from groundwater sources from boreholes and wells. Many of the supply arrangements date back decades when this localised industry was at its height, and the supplies were used for irrigation. The water from these supplies is today used primarily for the domestic needs of workers, the majority of whom live on site as migrant communities in temporary accommodation, such as caravans and mobile homes. The local authority found no evidence to suggest that the water was being used to wash the crops once it had been harvested. The source water in most cases was being pumped from a borehole or well to a large elevated steel tank from where it was distributed via a myriad of pipework and storage facilities, with poorly constructed connections above and below ground using products, some of which were potentially not approved for use on potable water systems.

Figure 18: Water tower

In early 2015 a local authority contacted the Inspectorate for support and guidance going forward with their duties as regulators of these supplies. The deadline for local authorities to complete risk assessments of private water supplies within the first five-year period since the implementation of the Regulations was approaching (December 31 2015), and they were concerned that progress to deliver was being hampered by a number of issues that were arising as they started to tackle the task in hand.

On meeting with the local authority in June 2015 it became apparent that this task presented a number of challenges, not least that previously unknown supplies were emerging all the time and that the configuration of supply systems were, in some cases, complex to risk assess.

This was in part due to the resistance of site owners to either fully cooperate with their investigations, or appreciate that simple makeshift repairs did not constitute adequate mitigation of risk when presented with action plans. In addition the pipework arrangements were in most cases lengthy, poorly constructed and concealed, and often shared sites with pipework providing water derived from public supplies, which could not easily be differentiated from those on the private supply. Of those supplies visited by the local authority, all were described as having a range of risks from the source to the point of consumption, many of which suggested a risk to human health. This included boreholes that were in a state of poor repair and were not adequately protected from vermin or the elements and the absence of treatment (or adequate treatment) to mitigate catchment risks, such as historical landfill sites, agricultural farming and animal husbandry (stables, kennels etc.) practices, unauthorised ‘cottage industries,’ such as car repair and breaking yards, and where illegal discharges were occurring.

The Inspectorate advised that they appeared to have sufficient evidence from their visits to enforce under Regulation 18 and should not delay in serving Notice at the first opportunity. Inspectors were invited to accompany the local authority on site to further advise and examine some of the supplies in question – a visit they duly undertook in October 2015.

During one of these visits, the Inspectorate identified that a Regulation 8 supply had been created on one of the sites, where a site owner was further distributing water from the public supply via his neighbour’s premises to provide water to newly constructed buildings with bathroom facilities on his own premises. This apparently illegal connection was later reported to the local water company by the Inspectorate. On this same site water was being supplied to caravans from a borehole located within the growing area of the greenhouses surrounded by crops. This was pumped to a poorly constructed elevated steel tank, as is common practice on such nursery sites, and distributed through pipework, in places held together with standard household tape. The pipes were, in part, laid through open ditches alongside cluttered working and living environments. The water was fed to a large storage tank located directly beside a hand dug foul water waste pit covered loosely by wooden boards and receiving site sewage. From here the sewage was being pumped directly onto a neighbouring field, located less than a 200m from the borehole. A Regulation 18 Notice has since been served on the relevant persons to fully mitigate the risks to human health.

Figure 19: Waste pit

Figure 20: Pipework laid in ditches

The Inspectorate observed the site and found it was poorly maintained. There were disregarded produce heaps in a state of decay, untidy and messy fuel and other stores, and undesirable localised activity in close proximity to water storage areas. Boreholes were seen to be unprotected, and in one case directly adjacent to a neighbouring stable, toilet block and septic tank. Elsewhere water was being supplied for domestic purposes via a small service reservoir with no protection from vandals and wildlife, with clear routes of ingress evident.

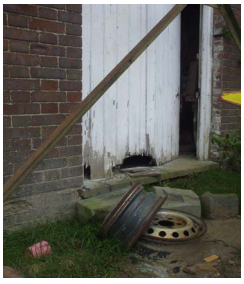

Figure 21: Entry to borehole shed

Figure 22: Borehole headworks

Figure 23: Headworks for borehole

Figure 24: Water storage tank

This case study illustrates the number and scale of water quality risks that can, and as these examples show, have developed over time on private water supply systems through neglect and poor management prior to the implementation of current national legislation. Prior to 2010 local authorities monitored supplies according to the frequencies laid down in the 1991 Regulations to determine whether or not a supply was compliant with standards and therefore safe to consume, or not. A satisfactory sample result, however, is no guarantee that the supply affords no public health risk at all times, and clearly as this case study illustrates, risks can be prevalent and increase with time, irrespective of what sample results might indicate. Since 2010 local authorities have been empowered to enforce where there is evidence of an unwholesome supply and/or where actual and potential risk to human health has been identified via the risk assessments they are required to undertake under Regulation 6. The Inspectorate is aware that in some cases local authorities are still reliant on monitoring to guide their actions to enforce. Local authorities are encouraged to apply their powers to protect consumers by a timely proactive risk-based approach.